By Alex Robinson

The idea that slavery was benign and that the enslaved were content was part of the myth disseminated by plantation owners who argued that slaves did not want to be free. Mary Prince, the first enslaved woman from the Anglophone Caribbean to write her biography was infuriated by this lie:

“I am often much vexed and feel great sorrow when I hear some people in this country say that slaves do not need better usage and do not want to be free. They believe the people who deceive them and say the slaves are happy. How can the slaves be happy when they have the halter round their neck and are disgraced and thought no more of than cattle. It is not so. All slaves want to be free. To be free is very sweet.”

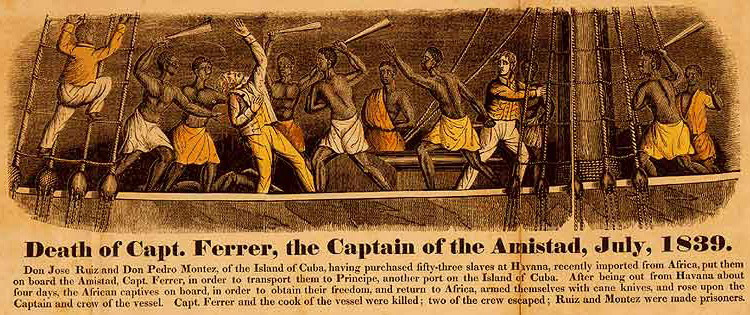

The truth was that escape was on the mind of all who were enslaved from the moment of capture and the first recorded rebellion took place in 1521 on Santo Domingo. Maroon communities of runaway slaves existed in most Caribbean islands and most famously in Jamaica. Over 10,000 escaped slaves evaded capture in Brazil for virtually the whole of the 17th Century. Ten percent of slave voyages recorded rebellions, the most famous slave ship revolt being the Amistad in 1839. Slave rebellions were not reported since this would undermine the myth of the ‘contented slave’. The revolution in Haiti (1791-1802), which resulted in the establishment of the first free republic of former slaves, terrified contemporaries but, like other reports of African resistance, it dropped out of history, until the black Trinidadian historian C.L.R. James revived the story in The Black Jacobins in the 1930s.

The repercussions from better armed and ruthless dealers and owners carried a risk of death, so revolt required huge courage and resourcefulness. In 1712, about twenty-five slaves with guns and clubs set fire to houses on the edge of New York City. Afterwards, eighteen participants were savagely executed – some were burned alive, some broken on the wheel, and others subjected to tortures.

Rushton’s first anti-slavery poem – The West Indian Eclogues – shocked even his abolitionist friends. He describes an enslaved African planning revolt and taking revenge on his master, who has raped his wife. In Toussaint to his Troops he writes in the voice of the black general exhorting his troops to rise up against the white oppressor. For Rushton his poetry was the nearest he could get to revolt himself, and was a way of justifying and celebrating black resistance.