‘Rushton the Poet’ extract from the book by Dr Franca Dellarosa: ‘Talking Revolution: Edward Rushton’s Rebellious Poetics, 1782-1814. (Liverpool University Press, 2014.)’

Exploring the range of Rushton’s poetic world leads the reader right to the heart of the Age of Revolution – the worldwide turmoil over the decades between the end of the eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries, when revolutionary uprisings would flare up throughout Europe and the Americas. Rushton’s poetry records from below and maps out this complex transnational geopolitics of disorder and resistance, which took shape at the time in which the modern notions of class, nation and race were being formed – both as concepts, and as historically defined realities, too often drenched in blood. This is all Rushton’s concern – that bloody history surfacing from the writings of a radical poet, editor of a paper and bookseller, but also a sometime destitute ex-sailor and a blind man for most of his life – he himself embodying a catalogue of social exclusion.

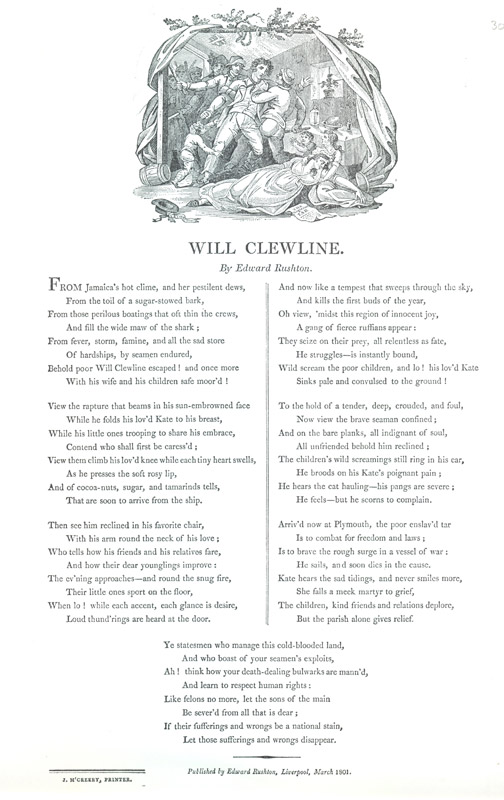

A process of sympathetic identification with the dispossessed and highlighting of their potential for agency are central to what we can describe as Rushton’s ‘rebellious poetics,’ and are consistently reflected in the modes of his poetic language, too. Rushton’s writing indeed bears testimony to the unspeaking majority, constructing an alternative narrative of world politics, domestic social conflict and power relations at large. He performs his task with the tools of the trade. He experiments in the popular ballad form or the more technically demanding form of the eclogue, both unmistakable markers of the late eighteenth-century language of poetry. In Rushton’s hands, these forms are flexible instruments, which he consistently and deftly remoulds in order to subvert those power relations and give voice to the voiceless – whether they be enslaved Africans toiling in West Indian plantations or on board slaving vessels, or the Liverpool sailors victims of the press gang (the forced recruitment of sailors to crew the Royal Navy warships); the enslaved rebels of the Haitian Revolution, or the Irish or the Polish insurgents. Bear in mind some of his titles: West Indian Eclogues (1787); “The Coromantees” (1814?); “Will Clewline” (1800); “Toussaint to His Troops” (1802?); “Mary Le More” (1798); “Lines Addressed To Robert Southey” (1814).

The reciprocal mirroring of politics and poetics – the sense as well as form of the words used to express it – is the one veritable constant, in Rushton’s idea of poetry, and can be traced pervasively as the drive that steers his treatment of his crucial concern – the human dignity of the silent majority, contrasted with the sheer brutal exercise of power – wherever in the world this may occur. While he is not interested in theorizing about poetry, he does have a poetic project, which is highly political. From his labouring-class stance, he originates from below a poetic programme centred on a vindication of human dignity that brings about a questioning of class, or race, and occasionally even gender hierarchies. Characteristically, this results in the attempt to give voice to the voiceless – to move the margin to the centre – and shapes his use of poetic form.